THE NORTH-EAST

CHANTRY CHAPEL,

OR ST. ANN'S CHAPEL.

Stepping down one step out of the chancel brings us to this chapel. This is the chapel which I allot to the Chantry of St. Ann founded by Dean Cosin in 1509. Of course there was formerly an altar here under its East wall, but it is gone. It went at the time of the Reformation when masses and prayers for the dead were forbidden, and chantry chapels consequently lost their uses. Though

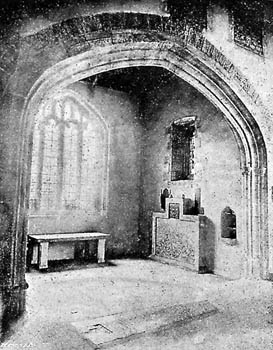

THE N.E. CHANTRY CHAPEL, SHOWING THE HODGES MONUMENT.

the altar is gone, yet the piscina which was a necessary accompaniment to the altar remains. I discovered it and opened it soon after I came to Wedmore, before the restoration of the church in 1880. The use of the piscina was to carry off the water which had been used for cleansing the chalice. The rose in this piscina shows it to belong to the Tudor period. The Tudor family gave England three kings and two queens, viz., Henry VII., Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary and Elizabeth. These reigned from 1485 to 1603, and within that time the chief work of the Reformation was done. Within those limits then must lie the building of this chapel. But as the uses of chantry chapels were forbidden before 1550, the building of this chapel is narrowed down to the first half of that period, viz., between 1485 and 1550 And that agrees very well with the date 1509 which I have arrived at by another method.

The small window at the East end of this chapel was blocked up till 1880, when we re-opened it. My mother was good enough to fill it with stained glass. The figure of St. Mary was chosen, though it should have been St. Ann. Amongst the material that had been used for blocking up this window were portions of an old stone altar, probably the altar that belonged to the chapel, or possibly the altar that stood in the North transept before this chapel was built. Apparently the altar after ceasing to be an altar had been used as a tombstone as there is a black-letter inscription running round the rim, which I cannot read. These fragments have now been put away in the upper of the two porch rooms.

The stone slab which has been set up in this chapel on modern legs is not an altar, but a tombstone that was found under the pavement in 1880. I forget exactly in what part of the church it was found. The inscription on it will be found further on with the rest of the inscriptions.

There is a good painted roof to this chapel though not in very good condition. The painting represents some of the verses in the Te Deum.

The Hodges Monument in this chapel had to be considerably cut down in 1880 in order to reopen the East window. We had the less scruple in doing this seeing that it had already been altered before. There is reason for thinking that it once stood in the North transept, under its East arch. The Hodges family were one of those numerous families who got some land and increased their wealth through the Reformation. The Reformation not only altered the doctrines and changed the service of the church, but it also set free an enormous quantity of land and sent it into the market. By dissolving the abbeys and chantries and religious houses of all kinds, and by clipping the wealth of those religious institutions which it did not altogether dissolve, it sent an enormous quantity of land into the market. I have already pointed this out in this volume of the Wedmore Chronicle, p. 41. And this is what seems to have often happened. When a lot of land was set free and sent into the market which had formerly been tied up in the hands of a church that never died nor sold, then some wealthy man would buy it wholesale and sell it retail. He would buy it as a publican buys a hogs-head of ale, and sell it as the publican sells a glass or a pint. He would buy it as the butcher buys an ox, and sell it as the butcher sells a few lbs. of beef. He would get hold of the great possessions of some dissolved religious house, and then sell it in small portions to smaller men (p. 46). I have already mentioned Sir Thomas Gresham, a wealthy Londoner, who bought great quantities of the church lands, and then retailed them. The manor of Wedmore got into his hands. Its first owner after that the Deans of Wells lost it was the Duke of Somerset, but he was quickly beheaded, and eventually in 1559 it was sold to Sir Thomas Gresham. Mr. Emanuel Green's very useful paper describes the belongings of the manor as consisting of 15O messuages, 50 tofts, 10 mills, 10 dovecots, 200 gardens, 2000 acres of [plough] land, 3000 acres of meadow, 2000 acres of pasture, 200 acres of wood, 1000 acres gorse, and £8 rents in Wedmore held in capite. The park of the manor had already, 1O years before or so, been disparked and sold separately, and I presume that the present estate called the Parks is a mark of that separation and represents the whereabouts of the old Manor park. Sir Thomas Gresham having obtained the Manor with the exception of the park, began to break it up and sell it bit by bit. To Thomas Hodges he sold the capital messuage of the Manor, or manor house as we call it, with some cottages, 3 orchards, 70 acres of land, 3 acres of wood, 100 acres of furze and heath. This was in 1577.

I believe this Thomas Hodges was already living in Wedmore or else at Allerton when he became possessed of the Manor house. Possibly he had occupied it when the Deans of Wells still owned it. He seems to have been a buyer of land, as he became possessed of Elm near Frome, and of Stream in the parish of Weare. He died in 1600, being buried on December 27th, as our Registers tell us. His wife Margaret survived him nearly seventeen years, "generosa, senex et vidua." His eldest son Thomas had died about seventeen years before him, killed at the Siege of Antwerp.

In the constant wars between Holland and Spain that were going on about this time, many Englishmen who sought an adventurous life, and hated the religion and the cruelties of Spain, and sympathized with Holland as a Protestant nation and as a nation struggling to be free, went over and fought for her. Among them was Thomas Hodges of Wedmore, junior. There he lost his life at the siege of Antwerp in 1585, and, as the inscription on his monument tells us only his heart was brought back home. I recollect when at Antwerp thirteen years ago going to some public building; I think it was a picture gallery. And as I was going upstairs I looked out of the staircase window and down upon some workmen who were demolishing a house and lowering the ground. And the soil was full of human bones, there was a great heap of them, the bones, I daresay, of Spaniards or Dutch killed in some one of the many sieges that Antwerp has had to undergo; and when I saw those bones my thoughts straight-way went to Thomas Hodges jun., under the shadow of whose monument I put on my surplice every Sunday, and I wondered if the owners of those bones had ever fought by his side or felt the thrust of his sword.

The Captain had married Agatha Podney of Westbury, and left a son, George, who succeeded his grandfather at the Manor House in 1600. He died in 1634. His effigy in brass will be seen on the monument. Col. Bramble in his paper on Wedmore Church says, "The effigy of George Hodges should be noticed, as being probably the latest instance of military costume on any brass in England. All armour, except the gorget still worn by officers in the French army, has disappeared; and the buff coat and modern sword hilt of the Caroline period will be noticed."

This George was succeeded by his son Thomas, who died unmarried in 1649.

Thomas was succeeded by his next surviving brother George, who died in March, 1655. His monument just round the corner in the chancel has already been mentioned. It was his widow who married Jeremy Horler, the Cromwellian Vicar of Wedmore. George had two daughters, co-heiresses, one of whom, Jane, married John Strachey of Sutton Court, near Bristol, the friend of John Locke, and eventually owned all the Hodges property. She died in 1727, aged 84. Her son John Strachey wrote a history of Somerset which has never yet been published. Sir Edward Strachey tells me that a good deal of it is now missing, including the Wedmore part. The Stracheys kept their lifehold property in Wedmore, the Rectory, etc., till about 1780, but they seem to have parted with the Manor very quickly. Certainly before 1700 it was in the possession of the Bridges family of Keynsham, I presume by purchase. It belonged to James Bridges who was created Duke of Chandos in 1719, and who was Handel's patron, and his son the second Duke sold it in 1757 to Messrs. Bracher and Thring, who sold it in 1808 to the late Squire Barrow. The Barrows had occupied the Manor house for some time previously.

SOUTH EAST CHANTRY CHAPEL.

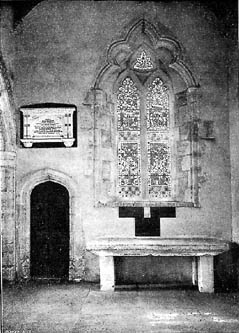

South-East Chantry Chapel, containing the decorated window and the old

altar.

Crossing the chancel we go down two steps into this chapel. For whose soul it was built and endowed and to what saint it is dedicated, I cannot say. But it would seem as if it were either the chapel belonging to the Chantry of Our Lady which was endowed by "sundry" Deans whose names are not given in the record, or else the chapel belonging to the Guild of St. Mary. I think the former of the two is the most likely. The altar is gone but the piscina remains. The altar which stands now where the altar formerly stood is the old high altar whose discovery has already been mentioned. The legs on which it stands are modern. The Decorated window which is over it I have already described. The doorway by the side of it led into the old Vestry room which we took away in 1880. That Vestry room was fitted up for the purpose in 1828, being formerly a lumber room, and used for the keeping of mad people in. It was a great blemish to the outside appearance of the church, and caused the lower half of the Decorated window to be blocked up. The doorway is a seventeenth century doorway, perhaps about 1630, and there is some difficulty in seeing what it originally led into. I know no more about it now than I did when I went into the matter seven years ago (Wed. Chron. Vol. II. No. 4, p. 168; No. 5, p. 217-220). The other door on the South wall of this chapel is (or was) the ringers' door, used by the ringers when they rung from the ground. It does not seem to be an original doorway, but an insertion.

SOUTH TRANSEPT

Moving a yard or two westward we come to this transept. Here stands the font. It was put here five or six years ago. Till 1880 it stood at the end of the South aisle up against the West wall of the Church. There is no record of its having ever been anywhere else. In 1880, acting on the advice of the architect the Restoration Committee moved it to a spot near the South door. But as that was found to take up space that was more useful for seats, it was afterwards moved to its present position, where it looks well. It belongs to the Perpendicular style of architecture. In his paper on Wedmore Church Col. Bramble suggests that the bowl or basin may have been originally square and of Norman or Early English date, and that the square may have been turned into an octagon by cutting off the corners in the Perpendicular period. The octagonal shaft on which the bowl stands is work of the Perpendicular period, and the step and minister's standing place belong to 1880.

On the West wall of this transept, high up and near where it joins the tower, will be seen a small arch. It was brought to light in 1880, being of course built up and plastered over till then. It is evidently a relic of the old church, but I have never yet seen anybody who could so much as guess at its original purpose, except that somebody once suggested a reliquary, i.e., a place for keeping relics in. It has occurred to me whether it may not be the sole surviving arch of an arcade that ran round the Early English or the Norman transept. Although the Early English church had transepts, yet very little of the original transepts can be left standing. The cutting of those arches through their East and West sides, and the lengthening and heightening of them, all done in the Perpendicular period, must have caused the original transepts to have almost entirely disappeared. The only original bits of them left standing would be where they adjoin the tower. That would agree with the position of this one arch. The large window at the South end of this transept is of course in the Perpendicular style.

THE TOWER.

As I have already said the lower part of the tower is the only bit of Early English work left as and left where its builders put it. It is the one bit of the church which you see to-day as you might have seen it about the year 1200. All else that was standing then is gone and has been rebuilt. It is obvious that the low arches of the tower and the lofty nave don't match each other. They don't gee together. The tower arch was never intended to have such a nave. The nave belonging to the tower was a much lower one with a steep roof. The tower cuts the church into two halves or rather into four quarters, which did not matter to those who built it, because they never wanted to use the whole church for one purpose, but which is a little inconvenient to us now, because we would like to. I have examined the tower closely on the outside to see if I could find a joint, which would show where the Early English tower leaves off and where the Perpendicular work begins, but no joint can be seen. From this it would seem as if the Early English tower, or at least three sides of it, was taken down and rebuilt from a little above the top of the arches, and that from there the Perpendicular work begins. The East or chancel side must have been left standing higher than the other three sides, because it bears the mark of the Early English chancel roof upon it. The octagon of the staircase turret does not come down to the ground octagonal as it is above, but has the lower part of its western and northern sides cased with masonry in a way that it is difficult to understand. It is on the western casing that St. Christopher has been painted. There would appear to be a joint visible on the turret where Early English work may leave off and Perpendicular work begin. It is visible inside the church over the door that leads to the top of the tower. This octagonal turret had a steeple, lead rolled round a framework of timber, till Squire Barrow thought good to take it away.

THE NORTH TRANSEPT.

Here is the organ, brought here in 1880 from the gallery at the West end of the church. It was built by Willis of London about thirty years ago. It succeeded an old barrel or grind organ, of which Mr. Taverner gives me the following account. It was built by Henry Bryceson, 5, Tottenham Court New Road, London. Its compass was from GG to G, forty-four pipes. It had six stops, viz., Stop Diapason, Open Diapason gammut, Principal, Twelfth, Fifteenth, Tierce. It had three barrels, each barrel having eleven tunes,

| BARREL 1. | BARREL 2. | BARREL 3 |

| Old 100th, L.M. | Sheldon, C.M. | St. James, G.M. |

| Easter Hymn, 7's. | Oxford, C.M. | St. Ann, G.M. |

| Islington, L.M. | Portugal New, L.M. | St. Stephen, G.M. |

| Hanover | Bedford, G.M. | Mount Ephraim, SM. |

| Devonshire, L.M. | Abridge, G.M. | Shirland, S.M. |

| Stockport, L.M. | Abingdon, G.M. | Pickham, S.M. |

| Angel's Hymn, L.M. | Zion Church, G.M. | Warwick, G.M. |

| Luther's Hymn, L.M. | Manchester, G.M. | London New, G.M. |

| Wareham, L.M. | Irish, G.M. | Bellefield, G.M. |

| Creation, D.L.M. | Cambridge New, G.M. | Sicilian Christmas, 7's. |

| Lockhart's | Evening Hymn, L.M. | Morning Hymn, L.M |

The church rate books show that this organ had been bought in 1828.

The large window at the North end of this transept is of the Perpendicular period. Heightening, lengthening, and cutting arches through its walls, have made the walls of the original transept almost disappear in this case as in the case of the other one.

In 1880 when the walls were stripped bare of their plaster, I saw, or thought I saw, that there was the appearance of the wall of the tower having been drawn to receive the arch into this transept, as though originally there had not been a North transept. I could not see the same appearance on the South side. I know not how this could be. A church with only one transept, like a unicorn, would have a strange look.

It is in this transept, before the North-East chantry chapel was built, and so before the East side of it was cut through, that I imagine the original altar of St. Ann to have stood, possibly the very altar whose fragments are now in the upper porch chamber; I mean the altar which is mentioned in the deed that records the founding of the Guild in 1449, and that is said there to have been on the North side of the church; it would have had to be taken away in 1509 when Dean Gosin cut through the wall against which it stood in order to build the chantry chapel. As he took away St. Ann's altar he could not do less than dedicate his new chapel to her, unless he wanted to incur her wrath.

THE NAVE.

Passing into the Nave we may first turn round and look up at the West side of the tower where the Royal arms are.

The Royal arms were ordered to be placed in every church (I am not sure exactly when), and I think might just as well, be allowed to occupy some place of dignity instead of being thrown into the coal-hole, as they very often are. Certainly they are quite as ornamental and sensible as some of the tawdry frippery with which churches are sometimes decorated.

On the right of the Royal arms we see a buttress high up. I think this buttress must originally have come down on to the South wall of the Nave, and so it shows us the width and height of the original Nave before the builders of the later part of the Perpendicular period pulled it down and built it up again higher, wider and longer than before. Of course before that was done this buttress was above the roof and only visible from the outside instead of being visible from the inside as it is now. But it shows us something else. As this buttress can be traced up to the top of the tower it must be a Perpendicular buttress, because the upper part of the tower is Perpendicular. But this buttress evidently existed at the same time as the original low and narrow Early English Nave. That shows that of all the various alterations which the Perpendicular builders carried out, the raising of the tower was the first, and the rebuilding of the Nave came afterwards. That brings the date of the raising of the tower into the early part of the Perpendicular period.

On the other side of the Royal arms will be seen something else that shows the height of the original Nave, viz., a string course or weathering or whatever the correct name for it is, on one of the sides of the octagonal staircase turret. This, for some reason or other has been cut about. Originally it must have been outside the roof.

The door close by, which looks now as if it were only intended to be opened by those who want to take a plunge out of life, must originally have led into a loft or gallery. Mr. Edward Wall has very acutely observed that the square stone in the first arch on each side of the Nave must have been put there to replace a beam when this gallery was removed. What this gallery or loft was intended for if not for mediaeval singers I cannot say. We have already seen that the rood loft was on the East or chancel side of the tower, and though it is possible yet it is not likely that there were two rood lofts. When this gallery was removed I do not know, but I should imagine not so very long ago, seeing that the tradition of it has not quite died out. Mr. Robert Morgan tells me a story which is rather vague, but which is definite enough to point to this loft. It is this, that a girl, who was a girl about eighty years ago, came in one day and said that her uncle had been into the church and seen someone "in the tallat," and the tallat is expressly said to have been the one we are now looking at with the eyes of our imagination and not the one at the West end of the church. But he is not sure exactly how the story should run and whether the tallat was actually there in the girl's time. Anyhow it is enough for us that the story contains a tallat which was at some time or other where we are now looking.

Just under this door (which was blocked up till 1880) is a mural painting of St. Christopher. I told the story of St. Christopher and gave an engraving of this painting in the first volume of The Wedmore Chronicle, and will not repeat it. I will only just say that the painting was discovered in 1880 when the plaster was being taken off the walls. Very little had to be done to it except putting something on it to prevent its scaling off, as it began to do when exposed to the atmosphere, and making good what had been chipped out to make a rough surface for the plaster to stick on to. There are evident signs that the painting has been twice repainted; each of the three paintings following its own lines more or less and not being exactly line upon line. So when one painting scales off anywhere, it reveals the former one beneath it. The representative of the firm of Messrs. Layers, Barraud & Westlake who came to repair it, said that the date of the latest of the three paintings might be about 1520, and the previous one about 1460. That would be bringing us near to the time when the nave was rebuilt. The latest painting is the most gorgeous in colouring, but the previous one showed more taste. Of the two heads of Christ, the one on the left (as you face the painting) belongs to the latest, the one on the right belongs to the former one. St. Christopher's head belongs to the former painting, the rest of him to the present one. The broad flat fishes belong to the former painting, the smaller fishes to the present one. All else belongs to the present one. Of course it will be understood that no part of the former painting should by rights be seen now and only can be seen when the latest one has scaled off When the painting was first discovered the head of St. Christopher which is seen now could not be seen but there was another head looking across in the opposite direction, in fact turned to the figure of Christ on the left instead of to that on the right. But that head quickly scaled off, and revealed the one which we can see now. I recollect very well the cap which was on the head which has scaled off, and it seemed to be something like the cap which is universally worn about the Basque provinces of Spain, but which I do not think is worn now anywhere else. Of the earliest painting of the three the traces are very slight indeed. They consist of two thin lines, one representing St. Christopher's nose, and the other representing the calf of his leg. But they must be hunted for before they can be found. The inscription above consists of a conversation between Christ and Christopher. I know the purport of it, it will be found in the story, but I cannot read each word. It begins, "Marvel not..."

In churches in Spain one very often sees an enormous painting of St. Christopher such as we have here. I believe he is sometimes found in churches in the East of England. Lympsham Church is dedicated to St. Christopher. As the custom of painting him in churches did exist, one is not bound to find any special reason why he should be painted in Wedmore Church. But I will just mention the following fact for what it is worth, without attempting to say whether it is worth anything or not. Very likely it is not. The different nations of Europe belong to different races or families of mankind. Welsh, Irish, French and others are Celts; English and Germans are Teutons; Danish and others in the North of Europe are Scandinavians. The story of St. Christopher is a Christian legend, a story which somehow got to be invented three or four hundred years after the time of Christ, and having got to be invented got also to be believed by Christians, and was believed by them for several centuries. The old Scandinavian heathen had in their mythology a story very much like it. They had a story of a gigantic big man named Wada carrying his son Weyland on his shoulders through deep water. And he is supposed to be called Wada because he waded, just as we see St. Christopher wading in the painting.

Now the first syllable of Wedmore is not very unlike Wada, and both may be derived from the same old word. In which case St. Christopher would not be out of place here. This may be only a coincidence, but it may also be something more. Suppose that the first painter of St. Christopher in Wedmore Church, four hundred years ago or more, had been familiar with this Scandinavian story, suppose that he thought that Wedmore was called after Wada just as many other places are called after Scandinavian gods and heroes, then he might have said, I must not paint Wada in the church because he was a heathen hero, but it will be very appropriate to paint the Christian Saint whose story was like Wada's. So up went St. Christopher where we see him now.

The pulpit just below St. Christopher is what is called Jacobean, i.e., it belongs to the time of James I., who succeeded Queen Elizabeth and reigned from 1603 to 1624. It was he who wasn't blown up on November 5th, and it was in his time that the Bible as we have it now was translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The pulpit had to be kept down in 1880 lower than it should be in consequence of the discovery of St. Christopher, who has also prevented there fixing of the sounding board. Till 1880 the pulpit, reading desk and clerk's seat formed what is called a three decker. Fragments of the two lower decks, Gothic and Jacobean, have been worked into the present reading desk.

At p.181, 182, will be found the notices of a Vestry Meeting called in December 1750 to consider the erection of a singers' gallery. Apparently there was some difference of opinion about it, and it took four years to get it up, p. 183. That gallery was subsequently enlarged and remained blocking up the West window till 1880. It was then taken down and choir seats were fixed under the tower. In November 1889 orthodoxy yielded to reason, and the choir was moved from under the tower where it could not lead the singing to its present position in the North aisle where it can.

Passing down the middle aisle of the Nave and looking at the pillars which part the Nave from the two side aisles, it will be seen how those on the one side differ from those on the other, both in the capitals above and in the bases below. The North aisle is said to be the latest of the two. The underpinning of the columns was done in 1880 in order to bring the floor to one level. How much the level formerly differed and rose as you went Westward will be seen by noticing how the underpinning increases in depth as you go Westward.

THE SOUTH AISLE.

This aisle, though in the same Perpendicular style as the Nave, yet is an addition made later on in that period. The original Perpendicular Nave had no side aisles. From the West end outside the church one can see the joint caused by the addition of this side aisle. One cannot see the corresponding joint caused by the addition of the North side aisle, because the buttress hides it.

At the East end of this aisle, near where it joins the South transept, is a something I know not what, which must be a relic of the original church. I always took it to be an original buttress, but the professional knowledge of Mr. Edward Wall assures me that it can't be a buttress. Whatever it is it is nothing now, and so must be a relic of the original church. It is just underneath one of the Boulting monuments. Originally it was outside the church, exposed to all weathers, but the alterations and enlargements carried out in the Perpendicular period have without shifting it caused it to be within. Perhaps one may look upon it as a sort of parable setting forth how some who are outside the church may without shifting them be brought within it. Enlarge the church as an institution; do to it what the men of the Perpendicular period did to the fabric. They enlarged, they lengthened and heightened and widened, and so what was without they brought it within, just as it was. They enlarged their boundaries so as to include it.

Notice where there has been an image of some saint in the arch leading from the South aisle to the South transept; but the image must have been put there late, because it is later than the arch, the arch has been hacked about to receive it, and the arch is not a very early one, no earlier than the South aisle, which is later than the Nave, which belongs, to the latest of the four periods.

THE SOUTH

CHANTRY CHAPEL, alias THE LADY

CHAPEL, alias THE OLD CHAPEL.

Two or three steps taken in a Southerly direction from the old relic, which was without but is within will bring us into this chapel. The altar is gone but the piscina remains. Where the altar stood is now a lofty marble monument setting forth the extraordinary virtues of the Boulting family.

The Boultings were one of those families to whom the Reformation did good, not merely because it freed them from the errors of Popery, but because it enabled them to get some land in their native place on which they throve. Soon after getting some of the Church lands which the Reformation threw into the market they built Theale Great house; 1670 is the date upon it; and it must have been one of them who had those curious paintings painted on the wall by the staircase which may still be seen there. I have for some time been intending to ask for leave to examine the title deeds and writings belonging to this house so as to make out its history; but somehow I have let the time go by when I might have done so, and if you don't do a thing when you can, it is not likely that you will do it when you can't.

But who founded and endowed this chantry, and who built this chapel that prayers might be said and masses offered in it for the eternal welfare of souls? And who is the Saint to whom it is dedicated?

One of its names, the Lady chapel, seems to be a local name, i.e., a name used by people in the place without thinking anything at all about it, and simply because they have heard it used by their elders; and therefore I presume that it represents a truth. If it were a name suddenly started by somebody or given consciously and deliberately, then it would have no great value. But being the name used unconsciously because others had used it before, that makes it likely that it represents a truth. And that truth would be the fact that it is dedicated to the Virgin Mary or our Lady as she used to be called.

I imagine that its other name, the Old chapel, also represents a truth, for that is certainly a local name and more commonly used than the other. But what truth does it represent? This chapel is not a bit of the old Early English church. Its style shows that it was built in the Perpendicular period, the last of the four periods. And it could not have been built very early in that period, because it was certainly built AFTER the South porch, and the South porch was built AFTER (or at any rate not before) the South aisle, and the South aisle was built AFTER the Nave, and the Nave was built AFTER the raising of the tower, and the tower was only raised in the Perpendicular period; so that throws the old chapel into rather a late part of the Perpendicular period. What truth or fact then is expressed by the name "Old?" I can think of three possible ones.

1. This present chapel may be the successor of a former one belonging to the same endowment, and so it may enjoy the name "Old" which would have been more strictly correct had that former one been still standing. Its doorway and two windows seem to have been made when the porch was built and not when it was built. But if there had been nothing there before the present chapel, then there would be no sense in them; so it looks as if the old chapel had a predecessor.

2. The name "Old" may belong to the chantry or endowment or foundation rather than to the building. There might have been a chantry founded or provision made for prayers being offered for somebody's soul without any chapel being specially built wherein to do it; and then if a chapel were built some years afterwards the name "Old" might get to be applied to it though strictly it only belonged to the endowment.

3. The name "Old" may be given to this chapel because there are two others in the church not so old. Everything is relative. If the North-East and the South-East chapels are later, then this one is relatively old, just as when there is a little girl of six years taking care of two other little girls of four and two, she is the old one.

At any rate, whatever may be the exact truth that this name "The Old Chapel" represents, I feel sure that it represents some truth, because it is a traditional name, it is a name that runs back some way, runs back to a time when they who started it knew what they were about.

I imagine that this chapel must be either the chapel belonging to the Guild of St. Mary mentioned above (p. 268) as being founded in 1449, or else the chapel belonging to the Chantry of our Lady mentioned above (p. 267) as being endowed by "sundry" Deans of Wells. I am afraid that I must leave the matter undecided, though I have little doubt that if Record Offices and Probate Offices were properly searched it would be satisfactorily cleared up.

There is just one thing more that I will say bearing upon this matter. It may in this particular case prove nothing, but even if it does not, yet it has a certain general value.

When I first came here in 1876 I recollect asking who sat in the Old Chapel; and I was told that a number of young men and apprentices did. Since then the church has been restored and re-seated and the seats differently allotted; but at that time the Old chapel, or at least a part of it, was not allotted to any house or family, but a number of young men and apprentices sat there.

Now it has occurred to me that that may be accounted for by the nineteenth century young men and apprentices being more or less representatives of the fifteenth century Guild. When in the middle of the sixteenth century, i.e., 1550, the Guild came to an end, and their chapel lost its original use and was thrown into the church, and the new kind of services were ordered such as required large congregations, then it would not be very strange if those who were more or less representatives of the old Guild went and sat in the old Guild chapel. And if they did that in Queen Elizabeth's reign there is no reason why they should not have gone on doing it till Queen Anne's reign a hundred years later; and if they did it in Queen Anne's reign there is no reason why they should not have gone on doing it till Queen Victoria's reign a hundred and fifty years later still.

If anybody looks into things at all, they will see how they go on age after age in some shape or other. They are not clean wiped out but go on in other shapes. Everything that is to-day has proceeded and resulted from something that was on some former day, and it bears some likeness to that from which it has proceeded, just as the son bears some likeness to his father. You may see some portion of the things of a former day in the things of to-day, just as you may see in children something of their parents. Somebody lately was describing some one to me who lived about fifty years ago, and after mentioning her various good qualities finished up by saying, "In fact you see something of her in so and so, mentioning a grand-daughter who is living to-day. And so it is both with things and people. In the things of to-day and in the people of to-day we see something of the things and of the people of a former day. And so I imagine that it is perfectly possible that the fact of those young men and apprentices sitting in the Old chapel in Queen Victoria's reign may have proceeded from the fact of their having sat there in Queen Anne's reign; and the fact of their having sat there in Queen Anne's reign may have proceeded from the fact of their having begun to sit there in Queen Elizabeth's reign, when services such as we have now first began to be held; and the fact of their having begun to sit there then may have proceeded from the fact of their being more or less representatives of the old Guild by whom and for whom the chapel had been built. But of course I am only saying what is possible and not something that I know for certain. I can say for certain where people sat in Queen Victoria's reign, but I cannot say for certain where they sat in Queen Anne's reign or in Queen Elizabeth's reign, because I was not there to see them. And I do not know for certain that the Old chapel is the chapel of the Guild; it may be the chapel of St. Mary's chantry founded by "sundry" Deans of Wells. I would just add that till the restoration of the church in 1881 the manor house pew was in the North aisle. The NorthEast chapel was the burial place of the Hodges family in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Probably the one fact was a result and continuation of the other.

As I have already said this chapel was built after the porch; when they built the porch they did not know they were going to make this addition. The two lofty arches (see the illustration on p. 290) between this chapel and the South aisle of the church were originally windows; the holes of the stanchion bars can be seen; and then when the chapel was built its two South windows were made the same size as these two, so that the tracery could be transferred from the one to the other, and these two remained mere arches as we see them now, the solid wall from the sill to the ground being cut through. Mr. Edward Wall has acutely detected and pointed out to me the old sills turned down and utilized as quoins where the wall was cut through.

The doorway into the porch and the window on each side of it were discovered in 1880. Having been built up and plastered over, their existence was quite unknown. Apparently they were made when the porch was built and not inserted afterwards when this chapel was built. That makes it look as if the old chapel had a predecessor, small and low, on the same site, into which this side door in the porch would be the only entrance, because the two arches into the church would then be windows, so that you could not enter that way as you can now. Some pieces of freestone which had formed the tracery of a window were found in the filling up of this side doorway and windows; they probably belonged to the window of the small and low predecessor of this chapel.

A hagioscope, or to use a more popular and expressive name, a squint, will be seen in this chapel; when it had to be repaired in 1880, I recollect that there was a difficulty in making out how it originally was. The object of the hagioscope was to enable the priest at the side altar to see the priest at the high altar when occasion demanded that he should be able to.

In 1880 there was found under the floor of this chapel a coffin-shaped Pennant stone of which I give an illustration.

Girl Unknown.

I cannot say that the illustration

is a very good one, and the grass around the stone is deceptive. It

is not in the churchyard, but was only carried out there to be photographed.

This is Colonel Bramble's description of it in his paper on Wedmore

Church:

"It is 27 inches long, 13 inches broad at the head

and 9 1/2 inches at the foot, and the edge except at the head has a

plain chamfer. On the slab in relief is a cross with fleurs de lis at

the terminations, and above the cross is the head of a girl with long

flowing hair bound with a fillet. There is no date or inscription, hot

the form of the cross indicates the fifteenth century, and the flowing

hair and fillet that the lady represented was unmarried."

I wish I could give a name to this girl who died while yet her hair was hanging down and before the days had come for it to be done up, and I wish I could say who were her parents and where they lived. But I am afraid I can't. Nor does one know whether the place where the stone was found in 1880 was over the place of her burial or whether it had at some time or other been flung there from some other part of the church. If one knew for certain that she was buried where the stone was found, then she and the old chapel might throw light upon each other, either upon other.

THE PORCH.

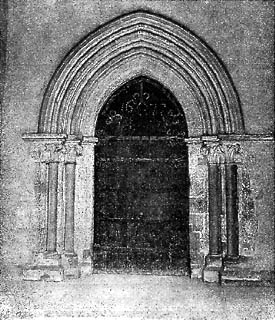

We have now got to the last of the group of buildings which make up the church, not last in date but last in the order in which I have taken them. It is more than a porch; with its two stories it amounts to a small tower. It belongs to the Perpendicular period, though, as I have already said, the beautiful inner doorway, of which I give an illustration, belongs to the Early English church, having been preserved and set up again further back when the body of the church was rebuilt in the Perpendicular period. Its original place in the Early English church might have been just six yards from where it is now in the direction of the North door. It is said to be very like the North doorway of the Cathedral at Wells. As Wedmore belonged to the Deanery of Wells, the same designer may have designed both, the same workmen may have set up both. The date of our doorway is between 1200 and 1300. The date 1688 on the door only belongs to the woodwork. The iron work is much older.

The two chambers over the

porch were probably or possibly intended for the chantry priests, whose

duty it was to pray for the dead in the chantry chapels that we have

been looking at, and who had nothing to do with the Vicar or Vicarage.

I cannot say that I should care to spend a winter's night in either

of them, certainly not in the upper one. But no doubt we are more delicate

and squeamish now than we used to be. Other uses for them are possible,

such as a school, a place for keeping records, etc. The Chantry of our

Lady had its own chantry-house, as the report shows which I mentioned

at p. 267, so the priest

of

Early English Doorway.

that chantry would not have needed to use the porch chamber.

When we were in the South aisle I ought to have called attention to a richly carved niche over the South door which now looks into the church. There was once a Saint in the niche, but the Saint is gone, probably pulled out and broken up either at the time of the Reformation in Henry the Eighth's reign or else a hundred years afterwards in the time of Oliver Cromwell. But this niche really belongs to the porch, because it was only in 1880 that we just turned it round and made it look into the church instead of into the porch room; with the exception of looking exactly the opposite way to what it did, its place is now exactly the same as before. One can hardly believe that it was intended only to be seen from the porch room. There are two alternatives. One is that there was an interval of time between the building of the South aisle and the addition of the porch, during which interval it would have been visible from outside the church. The other alternative is that there was originally only the upper room of the two, what is now the lower room being open to the ground, so that the niche would be visible below. Colonel Bramble favours this latter idea. I daresay we did wrong to turn it round, but it appeared to have been already tampered with, as the column below left off as abruptly then as it does now, which could not have been the original plan.

In the recess which was filled by this niche till it was turned round there is now a book-case, and in that book-case is a small collection of books. I gave a catalogue of those books in the first volume of the Wedmore Chronicle, p. 171 to 176, and at p. 368 will be found some account of how and when they became the property of the church. There is also there a series of rate books from about 1700, and a big Bible and Prayer books which were for the minister's use.

This room contains a chest with the usual three locks and filled with parish papers. My intention of sorting them and printing a list of them has never been carried out, and I am afraid that they are left rather in a state of confusion. The large and very heavy books relating to the enclosure of the moors need attention. The history of some pikes or weapons of some sort which are in this room I know not. I found them there. There are two whole ones and three points.

In the upper of the two rooms will be found as follows:

1. Some stones forming the tracery of a window which were found in 1880, having been used to block up the doorway and windows between the porch and the Old chapel. These stones may have belonged to the chapel which I guess to have preceded the Old chapel and stood on its site,

2. Some stones with black letter inscription which have formed part of an altar and then afterwards apparently been used as a tombstone. These were found in 1880, having been used to fill up the little window at the back of the Hodges monument in the North-East chantry chapel. They probably belonged to the altar of St. Ann.

3. Four stones which join together and make a chimney pot of the 15th or 16th century. These came from the Dean of Wells's manor house at Mudgley.

4. Some other stones found in the church. One, a portion of an arch and deeply moulded, seems to be of early date.

And now I think I have said all I know, and perhaps rather more, about the inside of the church, though there are still a great many points left undecided. There are one or two things one may notice from the churchyard outside.

FROM THE OUTSIDE.

Over the outer arch of the porch will be seen a niche containing the headless figure of a man. Who the man is or was I can't imagine. One would have expected the figure to be that of St. Mary, as the church is dedicated to her.

The little bit of pitching outside the porch is all that is left of a larger bit; at least I imagine that the following entries in the church rate book for 1720 apply to this spot.

|

£ |

s. |

d. |

|

| Pd for 17 lodes for the Casway |

1 |

5 |

6 |

| pd for halling the stones |

0 |

18 |

0 |

| Pd for pitching the caswaye being 120 yds. at 4d. the yeard |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| Pd the Masons for leving the ground for the foresaid casway |

0 |

4 |

0 |

| Gave the foresaid Masons likeer at several times |

0 |

4 |

6 |

On the gable end of the South transept will be seen a Tudor rose, which shows the lengthening of the transept to belong to the Tudor period. Close to that rose will be seen a head not in its proper position. It is an old head worked by masons of an earlier period and merely re-used by the builders of the Perpendicular period to which this end of the transept belongs. Had it been a stone of their own working they would have put it in its proper position.

The chancel is very poor work. The stones are small, and there is no set-off, or weathering, or string course, neither on wall nor buttress.

The ground on the North and West sides of the church was lowered about sixty years ago. Formerly you stepped down three deep steps into the church at the North and West doors. This accounts for rough masonry being seen which was not originally intended to be seen. The foundations of the buttresses which have thus been exposed to view are of Jew stone. I do not know whether this name of the stone is a purely local name or is used in other districts also.

FROM THE LEADS.

From the upper of the two rooms over the porch there is a door leading out on to the leads. When on the leads one can see a small quatrefoil window on the clock-face-side of the tower. It is now partly hidden by the roof of the South transept. Before the transept was raised this window would have been quite clear of the roof. There is a similar one on the North side of the tower, but that is completely hidden by the roof of the North transept, the North transept being rather higher than the South one.

From the leads it will be seen that the mouldings of the buttress at the SouthEast angle of the tower are rather different from the mouldings of the one at the South-West angle. The difference is in the third stage from the top. I make a note of this because these little differences generally mean something and will tell something, if we have ears to hear. I leave it to my successor to find out what this particular difference may tell.

Looking at the East side of the tower from the lead roof of the North-East chapel one sees the barbarity of the architect and his employer (the Dean of Wells), who hacked about that side of it in order to raise the chancel roof. When that was done I cannot say. Perhaps about a hundred years ago. The Cathedral records would probably show. One can also see from here signs of length and height added to the chancel walls. The additional height is much later than the additional length.

As I have already said no signs of a joint, no signs of new work continued on old work, can be seen on the tower; and yet we know for certain that the upper part is much later than the lower part. This proves that the joint must be inside the church, under the plaster, and probably in three sides out of four not very far above the arches.

The weather-cock and ball were set up in 1725, according to the Church Rate books for that year.

CHURCH FURNITURE AND ORNAMENTS.

The beautiful stained glass in the East window was a gift given in 1887. Messrs. Clayton and Bell executed the work.

The stained glass in the West window, executed by the same firm, soon followed it. It is a Memorial window to King Alfred and was erected by public subscription, though that does not mean that everybody subscribed to it. In the middle are full length figures of Alfred, William the Conqueror, Elizabeth, Victoria. These four sovereigns, two kings and two queens, represent one thousand years of English history. The intervals between them were respectively two hundred, five hundred and three hundred years. Under each of them are two scenes belonging to their times. Under Alfred is (1) The burning of the cakes; (2) Guthrum, the Danish prince, at Wedmore going through a ceremony which followed after baptism. Under William the Conqueror is (1) Harold swearing that he will never aim to be king of England; (2) The death of Harold at the battle of Hastings. Under Elizabeth is (1) Sir Walter Raleigh spreading his cloak for the Queen to pass over; (2) The Spanish Armada. Under Victoria is (1) Her Coronation; (2) Her family gathered around her. In the top of the window are the heads of Henry III., Edward III., and George III., the three kings who reached a Jubilee year. They were put in because it was in the first Jubilee year of Queen Victoria that this window was decided upon.

The other stained glass windows in the church are the gifts of individuals, all Scriptural, and mostly Memorial. Two of them (chancel and South-East chapel) are German. Wedmore Church will stand having any number of stained glass windows, so long as they are good. Hitherto we have been fortunate. But it is easy to be unfortunate.

The handsome brass eagle which spreads out its wings to serve as a lectern was the gift of Mrs. J. F. Bailey in 1881. It was the work of Mr. Singer of Frome. The Bible upon it, and Prayer book and the Service books on the Communion table were given by my mother in 1881. There is a predecessor of that Bible now in the Porch room. It has lost its title page, but the following inscription is on a fly leaf: This Bible was bought for Wedmore Church in the year 1680 by Robert Yeascombe and Roger Taylor, Churchwardens; Thos: Davies, Vicar.

The Communion plate consists of a large dish, a small dish or paten, a chalice and a flagon. The large dish has this inscription: The guift of Will: Counsell, of Stoughton, Gent., 1711. The flagon has this inscription: I.T: I.M., 1757. In the church rate account book under the year 1711-12 there is this entry: Paid for ye Communion Plate £11 : 13 : 2. I presume this applies to the paten and chalice. There are also two linen cloths with initials P. T. and J. W. Churchwardens, 1803.

Two Glastonbury chairs were given in 1881 for use within the Communion rails. Six oak alms dishes were also given in 1881. Seven dozen plain chairs have been bought this year, arriving from Wippell's at Exeter just in time to take part in the Festival of 1898. Their cost, £12, was paid by the balance of the King Alfred Window fund which had been lying for some years in P.O.S.B., and the proceeds of the sale of the old Vestry chairs.

The bells are eight in number. The treble and second were added in 1881. The inscriptions on them are as follow:

1. J. Taylor & Co., Bell founders, Loughborough, 188 I. [Weight 8 cwt. 1 qr. 4 lbs.]

2. J. Taylor & Co., Founders, Loughborough. Presented by J. F. Bailey, 1881. [Weight 8 cwt. 2 qrs. 11 lbs.]

3. Mr. John Tucker & Mr. William Brown, Ch. W., 1772. My treble voice makes hearts rejoice. [Weight 10 cwt. 2 qrs. 3 lbs.]

4. Lord how glorious are thy works. Bilbie cast me 1705. George Stone, Gabriel Ivyleafe. [Impressions of coins.]

5. Mr. John Tucker, Mr. Wm. Brown, Ch. W., 1772.

6. Bilbie cast me 1705. George Stone, Gabriel Ivyleafe. [Impression of coin of James II.]

7. John Barrow & George Green, Churchwardens. Ed Edwards do. Tho. & James Bilbie Chewstoke fecit 1801.

8. Mr. Peter Evans and Mr. George Vowles, Churchwardens, 1775. I to the church the living call, and to the grave doth summons all. Wm. Bilbie fecit.

The weight of the two new bells without their clappers is correctly given above; so also is that of the old treble, which went to Loughborough in 1881 to give the note for the new ones, and was then weighed. The traditional weight of the tenor with all its harness is 38 cwt.

The clock was put up in 1881. Its cost was £196, brought up to £220 by carriage and carpentering. Gillett and Bland of Croydon were the makers.

In this rough inventory I must not leave out the Parish Registers. But I need not say much about them here because they have been printed and published, and anybody can buy them who wishes to. The Baptisms have been published from 1561 to 1812. There are 11,873 entries spread over those 252 years, giving a yearly average of 47. The marriages have been published from 1561 to 1839. There are 3,732 entries spread over those 279 years, giving a yearly average of 14. The Burials will be found under the next heading.