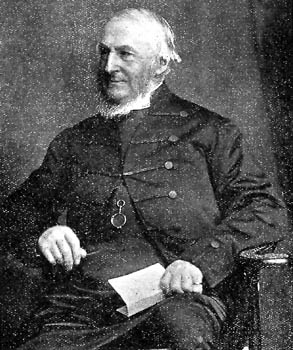

LORD ARTHUR

CHARLES HERVEY

Bishop of Bath And Wells, 1808-1897

Lord Arthur

Charles Hervey

It seems to me but a very little while ago that I was sitting down to make out a list of Vestry Meetings from the earliest times to put into the last number of the Wedmore Chronicle, with the intention of bringing out several more numbers in quick succession. But somehow since that last number came out seven years have slipped by, and none of those intended numbers have been written. In fact, the intervals between one number of this Chronicle and the next have often been so long that it is' wonderful how a second volume has ever been reached at all. And I think that the having to choose between so many subjects connected with the history of the parish is much more responsible for those intervals than any lack of subjects or material. There is no lack of that. If there was little choice, one would take what there was and sit down to it at once. But when there is so much choice, one hesitates between this, that and the other, and while one is hesitating weeks ans months and years slip by.

During this last interval of seven years my father has finished his earthly course. I put his portrait into this number of the Chronicle. It will not be foreign nor out of place there. As Bishop of this Diocese, as patron of this living, as one who was a frequent visitor here and took a great interest in the place, both in its present and in its past, both in its people and in its history, his portrait will not be out of place here. I will just add a few dates and facts.

My father was born August 20 th, 1808, at his father's London house, No. 6, St. James' Square. That house was built for a member of our family, a certain John Hervey, in the reign of King Charles II., more than two hundred years ago, and has been owned by the family ever since. When first built it was in fields outside of London; it is now right in the very middle of London, so great has been the extension of London on every side. I daresay there are few villages where some family has not owned the same house or field for two hundred years; but in London the changes are so enormous that this cannot happen often. My father was born in the original house, the first house that ever stood on the site, but that house was shortly afterwards pulled down by my grandfather and the present one built on its foundations.

My father's father was Frederick William Hervey, fifth Earl of Bristol, and first Marquis of Bristol. Though the title was taken from Bristol, yet there was no connection whatsoever with that place nor with the West of England, the family being a Suffolk one for now over four hundred years. Nowadays when a man is made a peer and takes a title, he takes it from some place with which he is somehow connected. But at one time it was the custom to take any title that had lately become extinct, connection or none. There were Digbys, Earls of Bristol, from 1622 to 1698; then they came to an end, and my father's great great grandfather, John Hervey, being made an Earl just afterwards, that lately extinct title was chosen for him. I suppose it did as well as any other, but it would have been more sensible to have taken one from the part of England with which he was connected, and not from the part with which he had no connection.

My grandfather was born in 1769, and died in 1859, being at his death only a few months short of ninety years of age. In his younger days he had been a violin player, and when at College about 110 years ago had often sat up of nights playing with Canning, who was afterwards a great statesman and Prime Minister. That violin he gave me when I was a very small boy, and I can recollect performing before him.

He had nine children, six sons and three daughters, who grew to maturity, and all but one have descendants living.

The eldest, Frederick William, 1800 to 1864, was in the House of Commons till his father's death; he was a Peelite, i.e., a Conservative who became convinced of the iniquity of the Corn tax and followed Sir Robert Peel. He was a most excellent man, with literary and archaeological tastes.

The second son, George, 1803 to 1838, was in the army.

The third son, William, 1805 to 1850, was in that profession on the top step of which is an Ambassador. He did not reach the top step, as he died comparatively young, but he was a man of very good abilities and character. He was also about the best amateur tennis player (not lawn tennis) of his day.

The fifth son, Charles, 1814 to 1880, was a clergyman in Essex. His activity and nimbleness have left an impression upon my mind. There was a very large larch tree in my father's garden in Suffolk, with great branches sloping towards the ground, and I have seen him run up it like a squirrel.

The sixth son, Alfred, 1816 to 1875, was in Parliament and held office at Court. He stood as a Conservative, but sometimes gave a liberal vote, which caused him to fall between two stools and lose his seat, first at Bury St. Edmunds, afterwards at Brighton. His eldest son is a clergyman in Norfolk, and has the Prince of Wales for a parishioner.

My father was the fourth of these six sons, and the last survivor of his family. His three sisters, Augusta, Georgiana and Sophia, married respectively Mr. Seymour, Mr. Grey and Mr. Windham.

For five years, 1817 to 1822, my grandfather and all his family lived abroad. On their return my father was sent to Eton school, where Gladstone was amongst his schoolfellows. Another schoolfellow, Colonel Pinney, of Somerton, in this county, has just passed away at the age of ninety-one years. After leaving Eton in December, 1826, my father went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was for over two years. By getting into the first class in the Classical Tripos he gave proof of good abilities and much industry. Letters written at this time by those who were over him speak very highly of his character.

In 1832 he was ordained a clergyman by the Bishop of Norwich, and immediately afterwards was appointed by his father to the Rectory of Ickworth, in Suffolk. To make this appointment possible he had to be ordained a priest within a month of being ordained a deacon. This was an ecclesiastical irregularity at which he would smile when he mentioned it in later life.

Ickworth was his first and last parish, for he remained there as Rector from the time of his ordination as deacon and priest in 1832 to the time of his ordination as Bishop in 1869. He only left it when he left Suffolk and came into Somerset to do the work of a Bishop. If he had not been made a Bishop and had continued there till his death in 1894, he would have held it for the long period of sixty-two years. I will therefore give some account of the place.

Ickworth is in West Suffolk, three miles from Bury St. Edmunds. It has been owned by the Hervey family, and has been their place of residence for over four hundred years. They first acquired it about 1470, coming there from Bedfordshire. The whole parish lies within a park of about 800 acres, into which no public road nor even a public path comes. Its great size, its beautifully undulating ground, its, stately old oaks, and about seven hundred deer, all combine to make it as lovely as anything of the kind can be. At the time of my father's appointment to the Rectory the number of houses in the parish was about ten, the population about sixty. It is still about the same.

Of these ten houses, one was a gigantic big house begun by my great grandfather, who was an Irish Bishop as well as an English Earl, Bishop of Derry. He died in 1803, before the house was habitable; but by 1832 the building was sufficiently advanced to enable my grandfather to move into it from the old mansion a few hundred yards off The move was made just about the time when the country was in a great state of excitement over the first Reform bill. My grandfather was against Reform, and consequently had the windows of his London house smashed. I am afraid that both sides sometimes smash windows though I think the Tories are the worst at it.

This move into the new mansion made the old one vacant, and it became my father's rectory.

The other eight houses were cottages scattered about the park for gardeners and gamekeepers. There was thus practically no village, i.e., no street, no school, no Rectory, nothing but the park containing two big houses, a church and eight scattered cottages. There had once been a small village, but that had been swept away in the time of Queen Anne. Only a pond called Parson's pond remained to mark where the Rectory had stood, and only an indentation in the ground marked where the village street had been.

My father's house being the former mansion was a better house than rectories often are, the rooms being large and lofty. Thinking it too big for a clergyman, he had some part of it pulled down when he first entered into it, though the arrival of twelve children in the course of years made it necessary afterwards to build again. There was a beautiful garden attached to it, though it would have been no great hardship to have had no garden at all in the middle of a park so private as Ickworth.

This is the place he came to in 1832 as Rector, though not of course as a stranger, not for the first time, for the days of his boyhood had been partly spent there. He was then twenty-four years old and unmarried.

Ickworth Church stood close by in the middle of the park; some parts of it were over six hundred years old. There was but one bell in the tower, and that had an American twang about it, as though it were crazed; but I must say that when I lately heard again its familiar sound on a Sunday morning calling the new big house and the old big house and the gardeners and gamekeepers to come and worship together, I thought that its sound could not have been more charming than it was.

In this Church there was always a Sunday morning service, and of late years, during the summer months, there was an evening service as well. The pleasant walk through the park often brought people to it from the neighbouring villages. A population of sixty, of whom about thirty were often in London or elsewhere, does not provide much material for a choir, but my mother's energy succeeded in getting some sort of a choir together which she led and accompanied. Sometimes a harmonium was wheeled backwards and forwards between our house and the Church, and sometimes my eldest sister merely gave the starting note on a concertina, and my mother, who had a powerful voice, carried it through. Of course I am speaking now of things within my recollection, say after 1850, and not of things as they were at my father's first coming in 1832.

Just outside the Churchyard wall, as near as the Manor house here at Wedmore is to the Church, there had formerly stood an old mansion which had been the residence of the owners of Ickworth for several centuries; it preceded the later mansion which had just (1832) become my father's house, just as that old house preceded the new and present mansion. I use the word mansion in the sense of a house occupied by the owner of the estate. About two hundred years ago the oldest of the three mansions had been deserted and allowed to fall to pieces; there is nothing of it now standing above ground any more than there is at Court Garden, Mudgley. But the foundations have been left in the ground not far below the surface, and in a dry summer the grass over them gets burnt up, so that you may trace the lines of the old house. Soon after coming to Ickworth as Rector, my father had carried on some excavations there and had made out the plan of the old house. That was before I can recollect. But I can recollect when we children sometimes strolled up there with him, and grubbed about and made small holes with our sticks and fingers, and sometimes unearthed a big stone. And I recollect one occasion when I was grubbi.ng away and making a small hole with a small finger and a small stick, my father contrived to slip his gold ring in, so that I might come upon it suddenly and think I had made a great discovery. I did come upon it suddenly, but I don't think I was taken in. This is a very small incident, but it helps to illustrate a feature in my father's mind and character, which was to be seen all through life and in all that he did, viz., the combination of earnestness and lightness, or of seriousness and humour. Nobody threw themselves into what they were about more seriously, more earnestly, more thoroughly, than he did; whatever it was he was doing he threw into it all he had; he could not do a thing half-heartedly, or flippantly, or triflingly, or with half his power, or without caring about the result; but at the same time he was never heavy or dry; be always had a light touch, and was ready for any little joke or humour, so long as the joke or humour did not interfere with the way in which the thing was done.

Since those days I have made other and deeper holes with stiffer fingers and stouter tools; those other and deeper holes made here in this West of England have given me much pleasure and caused much excitement; but none of them have caused greater pleasure and excitement than those little childish ones made in the east, when one was as it were going back into the chamber and presence of one's forefathers, and treading the soil which had been trodden by them, and hoping to pick up something which they had left behind.

Such a parish as this, a park with ten houses including his own and his father's, did not give my father much scope for work within it. But he had other parochial work. When he first came there the small neighbouring parish of Chedburgh was united to Ickworth and held with it. He also held the Curacy of another neighbouring parish, Horningsheath alias Horringer, and was Chaplain to the Gaol at Bury St. Edmunds. After a time Chedburgh was separated from Ickworth, and Horringer was united with it instead. From 1852 to 1869 he was Rector of Ickworth and Horringer.

Horringer lay just outside Ickworth park pales; its Church stands on the village green, hard by one of the park lodges; a part of the parish, though not of the village, lay within Ickworth park. Two Churches implied at least three full Sunday services in winter, and four in summer, which he and the Curate divided between them. Week-day services and isolated celebrations of the communion were scarce. Such things were less common then than they are now, and I don't think my father had much sympathy with them. My mother played the harmonium and also led the singing at every service in either Church, except when there were two services at the same time, and then of course she could not be at both. At first the Horringer school was the Horringer choir; but after a time we got a little more ritualistic, and the school children retired into a corner and a surpliced choir of men and boys took their place. A great deal of pains was taken with this choir. My mother was very fond of music, had a good voice and a good touch on the piano, and was musical. My father was not musical; i.e., he had that general intelligence and breadth of mind which made him see what a valuable thing music was, and which made him anxious to promote it everywhere, he had good taste and a perfectly correct ear, which made him able to detect if anything was done in bad taste or out of tune, and he had a bass voice, but he had nothing like a passion for music, and he had a difficulty in learning the bass part of a simple chant or hymn tune. I can hear him now at a choir practice learning his part in a new tune, going all round the note, first a little above it, then a little below it, when it seemed to me that the right note was so simple and obvious that it was more difficult to miss it than to sing it. For an hour or so before each service my mother would sit down before the piano and play through the tunes over and over and over again; through a space of thirty or forty years I have a distinct recollection of hearing the tunes played through before service scores and scores of times, so as to make sure of them. I don't suppose that this was really necessary, as my mother was a good musician; but, like my father, she was not one to do things flippantly, or carelessly, or by halves.

Sometimes now when I go to a Church and hear the organist constantly blundering and playing wrong notes, it brings to my mind those tunes I heard played through so often, and I wish that all organists would be equally careful to avoid blunders. If blunders must be made anywhere, it is much better that they should be made in the voluntaries than in the accompaniments. Organists are often not near careful enough about how they accompany. They accompany too much, never letting the voices say a single syllable without them; they accompany too loud, drowning instead of accompanying; they play wrong chords, and think nothing of suddenly spurting and altering the time. I am thankful that here in Wedmore we have nothing of that sort. The accompaniment is always accurate and in good taste, and kept within bounds.

I cannot leave Ickworth and Horringer without some allusion to its cricket club. My father never played in a cricket match within my recollection, and I don't suppose that he ever did so after being a clergyman, but he sometimes came out and played for a short time with us boys. I recollect his action in bowling. It was evidently the action of cricketers of his younger days, seventy years ago or so. It was not overhand bowling, where the arm goes right up as high as it can and bumps the ball down on the ground; I am old enough to recollect that style coming in. It was not round arm bowling, where the arm goes high enough to be at a right angle to the body but no higher; that is an older style than the overhand; I got into it forty years ago and have never got out of it, but I see very few left in the field who bowl that way now, which reminds me that it is time for me to give up. And it was not plain underhand. But it was a sort of half-way between underhand and round arm, i.e., when the ball was delivered the arm was about half-way between hanging straight down and being at a right angle. It was delivered with a little jerk, was of a medium pace, and there was a good break, though I don't recollect now which way the break was.

Of course, amongst us boys and the households of the two houses in the park there was constantly cricket going on somewhere in the park or garden. But it was not till after 1860 that we formed a regular Ickworth Club, and pitched upon a spot in the park to play on which has the making of as fine a cricket ground as any club could wish for, being a dead level, sheep-fed and mown, with short grass and no trees in the way nor boundaries of any sort. Such of my brothers and cousins as might be at home and a young gamekeeper or two were all that Ickworth could supply for matches; Horringer sent its schoolmaster and one or two others; no village team is complete without a schoolmaster; my father's former parish of Chedburgh sent a publican, a very keen and steady player; the West Suffolk Militia Barracks at Bury St. Edmunds sent a sergeant or two; one of them, Horsley by name, never missed a match; he was rather stout, but a very keen and useful player; he was an old soldier, bronzed by long service in India; he always walked in from Bury, arriving on the ground with military junctuality, instead of that slovenly slip-shod disregard for time which some cricketers seem to think is a part of the game. Sergeant Horsley nearly always played for us, but I recollect one occasion when he played against us; he hit a ball hard to square leg; my youngest brother, then a very small boy, was standing short leg and received it full on the forehead; he went down before it as a stump goes down when Kortright or Richardson hits it, and ought to have been killed, but somehow was not much hurt. If the ball had struck him a little more on one side or the other the result would have been different. Since then I have always thought that very small boys ought not to play with those much older than themselves. The rest of our players in matches were young gentlemen of the neighbourhood. We had a great many very pleasant matches with little or no squabbling. The matches were always whole day ones, beginning at eleven and drawing at seven, in the height of the summer.

I can only recollect one squabble, and that was soon settled and over. We were playing a club from Bury St. Edmunds, whose captain or secretary was one Neagus, a painter by trade. There was a Militia sergeant (not Horsley) who had been asked to play for both sides and had said yes to both. We found this out just as we were going to begin. I was captain of the Ickworth team, and Neagus and I proceeded to argue who should have the sergeant, contending for him as Jannes and Jambres contended for the body of Moses. My brother George was standing by, and seeing Neagus begin to get rather angry called out, "Hot Neagus!" and then with his hands on his knees laughed loud at his own joke. That did not make Neagus any cooler. However, the matter was soon settled, and the match proceeded very pleasantly and Neagus was most amiable. Neagus is a Suffolk name that I have never met with elsewhere.

I must not forget our umpire. He was an old man from Horringer, by name King. He knew the game thoroughly, and was as fair and good an umpire as one could wish to have. Being a poor man, we sometimes offered him a shilling for his trouble, but he always refused it. He was on the parish, and according to the wise rules of the Guardians in whose merciful clutches he was, if he had occasionally added anything to what they allowed him he would have forfeited his allowance altogether. One would have thought that they would have been only too glad for him to have done so. But no, they forbad it. Oh! the dense thickness of the heads which sometimes gather round long tables and make rules for others! Why don't they put themselves in the place of those for whom they are making rules? Would they then give an old man 2/6 a week and forbid him to add an occasional sixpence to it? They don't forbid sixpences being added if they are got by begging, they only forbid their being earned! My only cause of quarrel with our old umpire was when sometimes both sides agreed to shorten an interval and get out to play at once. We might do so, but I believe he would have gone to the stake and suffered martyrdom rather than go out one minute too soon or one minute too late. He was a great stickler for the exact letter of the law, and could not distinguish between those rules in breaking which you only break the letter of the law, and those in breaking which you break the spirit. The one may be broken if need be, the other may not be broken. But that not being able to distinguish between the two kinds of rules is a common thing, in cricket, in religion, in many other matters.

My father had been pretty good at high jumping. I have often heard him say that as a young man he could jump up to the height of his chin. As he was 5 feet 10 inches high, that was a very fair jump. But much more wonderful was the way in which he retained his spring to a late time of life. Between our house and the park there was a stout gate. I cannot say exactly when I last saw him go over that gate, but I distinctly recollect seeing him do so after I went to College, when he must have been close upon sixty. I am sure that not one man in a million would at the age of sixty have such a combination of pluck and spring, the one to send him at that gate, and the other to carry him over it.

My father had been one of the best amateur tennis players (real tennis) of his day. A small challenge silver racket and chain, which was played for annually in London, was won by him three years following, about seventy years ago, and so kept. One of my brothers has it now. I have heard him say that his brother William was rather better than himself, though they could play a good game together. The game of real tennis is very little played or known, there being so few courts. London, Oxford and Cambridge, have two or three courts each, and there are about half-a-dozen private houses containing one. The game is one that requires much head work as well as bodily activity. As soon as my eldest brother was big enough to toddle my father put a racket into his hand, and taught him to play a sort of tennis on the lawn. This game we all constantly played at Ickworth long before lawn tennis was invented. The fruit of the racket put thus early into my eldest brother's hands was seen a few years afterwards in the fact of his being one of the two players chosen to represent Cambridge against Oxford. For some time after we came to Wells, and when he was long past seventy, my father would come out for an hour or so and play a set of tennis on the lawn. He kept his beautifully correct form as an old tennis player to the last, and the severity of his strokes and the accuracy of his return were simply wonderful. When he played he played, i.e., he played the proper game in a proper way, and with all his might; he did not knock the balls about anyhow, or keep up a running conversation all the time, as the manner of some is, but his whole attention was given to the game, and any unnecessary interruption was resented. I recollect an absurd thing once in his early days as Bishop. He was playing tennis in front of the palace, and had just loudly called out the score, "deuce," when an elderly clergyman was seen coming up to call. Tennis was not so well known then as it is now, and my father hoped that the clergyman would not go about telling people that he had heard the Bishop using bad language.

He had learnt real tennis in Paris from professionals, and the advice which they gave him he gave to us when playing lawn tennis. One bit of advice that was being constantly given to us was to stoop when we played the ball; not to hit it when it was high up in the air, but to let it drop to within a foot or two of the ground and then stoop and return it. Anybody who has tried the two ways, stooping and not stooping, will see the value of this advice. Baissez vous, Baissez vous, the French professionals had cried out to him when he was a boy, and Baissez vous, Baissez vous, he in his turn cried out to us. Another bit of advice was to try and be where the ball was likely to come, and not stand anywhere, and then have to rush after it; and he used to tell the story of a French professional who so exactly judged the spot to which his adversary must return the ball, that he was always there ready before it; and a French gentleman seeing it asked very simply, "Why does the ball always go to where you are?"

My father gave up anything like sport when he became a clergyman, but he continued to be fond of riding and driving to a late period. On horseback he had a military seat, riding long in the stirrup, and always looking his full height. He was a dashing and fearless driver, and his visitors at Wells were driven by him to all sorts of inaccessible places. He always gave a fair price for his horses, and had good ones, which together with his good management of them may chiefly account for his seldom having any accident.

I have said that when he was appointed to the Rectory of Ickworth in 1832, he was unmarried. Perhaps I should have said sooner that after nearly seven years of single life at Ickworth he married Patience, daughter of Mr. John Singleton. This was in July, 1839. The fiftieth anniversary of the wedding-day was celebrated at Wells in July, 1889.

My mother's father was born in 1759; he was born a Fowke, but took the name of Singleton the very year that he was born. And that came about in this way. In the early part of the last century a certain John Fowke (whose mother was a daughter of Sir Humfrey Sydenham, of Chelworthy, in Somerset), moved out of England and settled down in Ireland. He married Patience Singleton, whose brother, Henry Singleton, was Lord Chief Justice of Ireland. They had a son Sydenham, who was my grandfather's father. Lord Chief Justice Singleton dying unmarried in 1759, left a part of his Irish property to his nephew, Sydenham Fowke, who thus took the name Singleton the very year that his son John, my grandfather, was born. My grandfather afterwards bought a house charmingly situated on Hazely Heath, in Hampshire, not very far off the great road from London to Basingstoke, etc. A younger brother of his was grandfather to the Rev. James Sydenham Fowke Singleton, Vicar of Theale.

But I must push on. These small parishes, Ickworth and Chedburgh first, Ickworth and Horringer afterwards, did not give full scope for one with so much life and energy and with so many abilities as my father had. The neighbouring town of Bury St. Edmunds gave him a field for further and voluntary work. He also always had some literary work at which he was engaged, Biblical, historical, genealogical, and so on.

In 1862 he was appointed Archdeacon of Sudbury, which of course did not take him away from Suffolk nor from Ickworth.

In 1869 he was appointed by Mr. Gladstone to the Bishopric of Bath and Wells, which of course took him away from both. I recollect, as though it were yesterday, the coming of the letter which offered him this promotion. I happened to come down first in the morning and saw a letter with the initials W. E. G. in the corner. As there was a Bishopric vacant at the time, and as my father had for some years been considered as likely to be promoted, I naturally guessed what that letter from the Prime Minister might contain. He was away from home, but was coming back that same day. My mother drove to the station at Bury to meet him, taking the unopened letter with her. I can see the carriage returning across the park with them. I stood at the gate, the gate I had seen him jump over not very long before, and his nod and pleased expression as he passed through plainly told me that the offer of a Bishopric had been made to him. The Bishopric was that of Bath and Wells. Soon afterwards the Bishopric of Carlisle became vacant, and Mr. Gladstone wrote to offer him that if he preferred it. But he had accepted Bath and Wells, and did not wish to change. So he came to this diocese in December, 1869, and therein lay his work for nearly twenty-five years. He died on June 9 th, 1894, aged 85 years and nine months.

I will say nothing of his life and work as a Bishop, but will confine myself to this short account that I have given of his home at Ickworth. I will only say that the multitudes who were present at his funeral at Wells, and the noble monument which the diocese has erected in the Cathedral to his memory, bear witness to work well done and generously appreciated.

I have said more than I intended to say. When I sat down I only intended giving a few bare dates to accompany the portrait. But when one begins to look back and draw upon one's memory, it is always difficult to restrain oneself. The tendency is to put down everything that one can recall. This going beyond my original intention must be my excuse for the lack of order, and especially of proportion, in what I have said.

I should like in conclusion just to set down anyhow a few qualities that I think my father possessed.

He was accurate, careful, and painstaking rather than brilliant and quick. He had not the breadth of mind and wide sympathies which enable one to understand those who think very differently to what one does oneself; I rather think that the boundaries which enclosed his power to understand other opinions than his own were narrower than they need have been but he had other qualities which kept him from bigotry or narrowness. Within certain limits he was tolerant. He was very just, and had nothing of the tyrant in him. He was considerate, always recollecting that what was due from others to him was likewise due from him to others. "Let us put ourselves in their place," I have often heard him say when discussing anything, and he generally did it, though I think there were some cases in which he was less able to do it than in others. He had a judicial mind, though again I think there were some matters in which he was less able to be judicial than in others. He was as high principled and honourable as a man could be, no schemer, perfectly open and straight, and simply incapable of anything mean, false or tricky. His mind was clear and exact, free from slovenliness and confusion. He was always calm and cool, neither excitable nor phlegmatic. His temper was very even. He could be angry, but his anger was never violent, and always under control. It consisted rather of an exceeding grave and serious manner, which was more full of awe than a mere torrent of loud words. I should think it must always have been rare for him to lose either his head or his temper. He was strong in habitual self-restraint and self-control, stronger I think in that than in self-denial. He was shrewd and sensible, and had much tact and good judgment. He was not of a suspicious nature, and was not a quick discerner of character. He had not a very good memory, and was not a great devourer of books. What he read he read thoroughly, and so deliberately. I don't think he ever skimmed a book. He was thoroughly practical, and never exaggerated. He had that general intelligence which made him appreciate and try to promote every branch of learning, but his own tastes were chiefly archaeological. He had a strong sense of humour, and he could tell a story well. He was liberal without extravagance, and thoroughly enjoyed dispensing hospitality. He enjoyed seeing others enjoy themselves, and the bicycle movement always interested him very much from its beginning. He was not very methodical in the arrangement of his letters and papers; but this deficiency was amply supplied by my mother, who kept them all in such perfect order that anything wanted could always be produced at a moment's notice.

He was essentially a man of moderation in all things. His place as regards parties was always in the middle, not because he deliberately chose a middle place as people for safety sake choose a middle carriage in the train, but because the disposition of his mind naturally took him there. In politics he was a Conservative; I cannot think of any question on which he took the liberal view or would have given a liberal vote; but he had some liberal tendencies which carried him a little in a liberal direction and away from the other end of his party. In church matters also he occupied a middle place. He had begun his ministerial life as an Evangelical, and though his office as a Bishop may have pulled him on a little, yet his views always kept something of their old evangelical character. He certainly never got so far as to regret the Reformation.

The various gifts and good qualities that he had were all there in due proportion; one was not great and another small. When you looked there was no one thing, whether talent or grace, that instantly caught your eye, and that overshadowed or over-balanced the rest, but you saw the assembly of many things in their just proportion. Together they made a harmonious and symmetrical whole. It was something like Salisbury Cathedral, which being all built at one time and in one style, is not beautiful in this part or in that part only, but as a whole. This is a type of character which has its disadvantages as well as its advantages, and the work of the world requires that there should be both types.

The mingled dignity and ease of my father's manners, his courtesy and pleasantness, always charmed those who met him. In height he was 5 ft. 10 in., active and well made, and though not heavily built yet possessing a certain breadth of shoulder. He always carried himself well. Though he probably could not have roughed it much, yet he was thoroughly sound and seldom had a day's illness. The youthfulness of his mind and his interest in everything that had interested him before, he kept to the very last day of his life. His activity of body he kept to a late period, but was crippled during the last few years of his life by something of a rheumatic nature. Though always engaged in literary work, even up to the last day of his life, yet he has not left many volumes of his own writing behind. His intense love of the Scriptures directed his attention towards them, and the archaeological turn of his mind decided which of the many points contained in them he should take up. It decided chiefly in favour of historical, genealogical and chronological points. He was proud of being able to say that he had taken a part in three great works that had come out in his time Dr. Smith's Dictionary of the Bible, The Speaker's Commentary, and the Revised Version of the Bible. The same turn of mind which made him write one book on the genealogy of his own family made him write another to reconcile the genealogies in Matt. I. and Luke III. His views on this last point were ingeniously worked out, and are, I believe, generally accepted. That same turn of mind made him see how valuable the numerous genealogies given to the Old Testament were for settling chronological points.

I have jotted these few points down anyhow, and here I will stop.